In 2001, Chris

Bentley and David Sisson spoke to E.C.

Tubb at his home in London.

.. |

|

How

did you become a science-fiction author? Well, that’s a long

story. During the pre-war years I was a

great reader. I read everything I could

that was to do with outer space, lots of

the old pulp magazines, Edgar Rice

Burroughs and all of that, and I really

just enjoyed it all very much.

Then, of course, the war

came along and lots of families broke up

for one reason or another. You were taken

away, put with people who you didn’t

know, taken to a place you’d never

seen before and told to fight. It was a

bit of a shake-up for you. Then, if you

were lucky, you came home and were told

to carry on where you left off. I came

back and didn’t know what to do with

my life. I thought to myself that a new

life in Australia might be an idea

because a lot of people were emigrating

there at that time.

I needed to have a trade to

get out there and because I had done a

bit of bomb damage repair work, I put

myself down as a carpenter. I wasn’t

really a carpenter but I knew enough to

get myself through an interview. The idea

was that I would go to Australia, get

settled, and then my wife would come out

a few months later. At the very same time

as this, I had a short story published

for which I was paid, and so I decided to

stay here and give it a go as a writer.

The chances are that if I had gone to

Australia, the wife wouldn’t have

followed me over and I would have ended

up getting killed by a sheep on a sheep

farm or something!

|

|

| This

first story was ‘No Short Cuts’ in 'New

Worlds' magazine? Yes. That’s right. It was my

beginning. I did other jobs to support my family,

but gradually I earned more money from these

stories. I had some ups and downs along the way,

but I managed to remain as a writer for the most

part.

I learnt that, more than anything

else, speed was everything. You had to write fast

- don’t edit, just let it flow. Sometimes

what you wrote was awful, but mostly it was

alright and you got away with it. If you were

paid by the word, you would use all sorts of

little tricks to fill the page. I had characters

spending a whole paragraph just stubbing out a

cigarette and going through a door. It was like

that in those days. Nowadays, if I was writing

like that, I would spend ages describing a

character using a mobile-phone or something like

that.

I learned a lot of things in those

early days. I was naive and I was ripped off once

by a bloke who claimed that he was better known

than I was and would be more likely to have a

story published than me. He told me that once my

story was published, he would give me the fee for

it and I would have my foot in the door, as it

were, with the editor of this particular

magazine. Of course, the bloke didn’t give

me any money at all and claimed that it was his

story. I learned from that.

Another thing I learned was from an

old mate, a writer called Bill Temple. He taught

me that characters should just ‘talk’.

They don’t ‘hiss’ or

‘bark’ or ‘snarl’ like in the

old silent melodramas - you know the kind of

thing: “Get over here,” the villain

snarled. I stopped using all of those ridiculous

adjectives and found that it sounded better.

|

|

Were

you just writing science-fiction? Oh, no. I wrote whatever I

could to keep the money coming in. I did

westerns, a few thrillers and some

gangster things, but it was the

science-fiction that I personally enjoyed

obviously. I began to write under

different names, some of which were given

to me by publishers as they were

‘house’ names - such as King

Lang, Gill Hunt and Volsted Gridban.

Once, when I was doing a magazine called 'Authentic

Science-Fiction', I actually wrote

everything in one particular issue,

including the readers column. I had

deadlines to meet and I just had to do

it.

They were great days because

I met some good mates who had similar

interests but I also upset a few people

too. There was one fellow who was

desperate to get in print. I was an

editor by this time and I published one

of his stories and it wasn’t bad,

but I had to cut down on some of the

weaker parts of the story. It still read

well but this bloke was furious that I

had done it and never spoke to me again.

|

|

| People have this idea that

writing is a kind of romantic life but it

isn’t. If you’re already well off and

write to express yourself I suppose it is

romantic, but for me it was hard work. I had a

family to support and really just sitting in

front of a typewriter makes it a bloody lonely

life, not a romantic one. You don’t meet

anybody and you lose touch with the real world

because you spend all of your time in one that

you have invented - such as the one for the

Dumarest stories. Sometimes it was nice to do

something different, to have a break from what

you were always doing. I spent some time selling

knives and demonstrating things in markets and

that type of thing. I actually really enjoyed

that and I felt a bit like a priest, telling

people ‘the truth’ and they would

believe me. It was the same with the writing. To

make a break from the norm was quite refreshing

sometimes. Were the 'Joe

90' Action Transfer books a

refreshing break from the norm?

That’s right, I did those,

didn’t I? I can’t remember exactly how

many I did, maybe two or three, but it paid

pretty well and I was pleased to be doing

something a little unusual. Because the stories

were based on a children’s television

programme, I was working under certain

instructions from the publishers. I couldn’t

have 'Joe 90' or any of the other

characters using excessive violence. I mean,

these were supposed to be adventure/spy stories

about a lad who had a gun and all of that, but

you couldn’t have him shooting anybody or at

least only do very little shooting. You had to

keep the stories simple. The characters all had

to be different so children could recognise them

as goodies or baddies. You also had to have

things that they knew from the programme itself.

I suppose it was quite a relief for me as a

writer because it saved me having to invent all

of these things.

|

|

How

were you briefed about the show? I think I was sent some

photographs and some outlines about the

characters - what they looked like, who

they answered to, what the car could do

and all of that - and then I just created

a simple adventure story around it all.

The 'Joe 90' books were sort of

comic strips so I had to write stories

which would translate into good pictures.

I did quite a bit of

freelance writing for comic strips too

but it was always the ‘real’

writing that I enjoyed the most. When you

were writing for a book or a comic that

had characters who had been created by

other people, you had to write with that

in mind. By this I mean that, for

example, Commander Koenig in 'Space:

1999' was someone else’s

character. I didn’t know him like I

do Earl Dumarest, who is my own

character, so I had to think about how he

acted in the actual programme but with a

little bit extra that I enjoyed putting

in there myself.

|

|

| Did

you find it creatively constricting to write like

this? To a

point, but I was used to writing like that. Back

in my early days, I was often given stories which

were part finished or only early drafts by other

writers. I had to fill the story out but still

retain the essence of what was already there.

Other writers did the same to some of my stories

so it was something that many of us did. You had

to put in your own ideas while still being true

to what the other writer had originally come up

with, so when I did the 'Joe 90' books

and the 'Space: 1999' ones I did it like

that. Of course, with the television books you

also had to write something which the reader, who

was also likely to be a viewer of the particular

programme, would recognise too. You couldn’t

just please yourself if you were writing for

books based on a film or a television programme.

People expected certain things from certain

characters.

Within the

realms of a science-fiction story, you still tend

to use factual scientific themes and concepts as

a basis to what you write.

Yes, that’s true. When I was

first writing, I used all of the things that I

had soaked up about the real universe and

astronomy and so on. I had read other

people’s stories with characters going to

different planets without spacesuits or breathing

equipment and I just thought it was all a bit

daft. I always wanted to make the stories

exciting and interesting but I didn’t want

them to be totally silly and outrageous. I knew

about rockets and the pressures that space flight

can put upon the human body so I tried to put all

of that into my stories. I always felt that it

was a little unfair actually. I don’t claim

to be a scientist myself, but I am a writer with

an understanding of science. Yet there I was,

earning the same as people who were just making

up everything with no regard to realism at all.

But that was how it was.

|

|

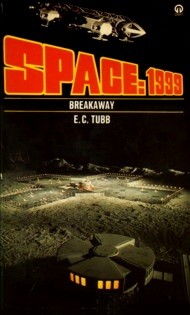

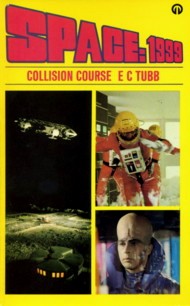

How

did you come to write the 'Space:1999'

novels? Well, I had the scripts

offered to me by a publisher who wondered

if I was interested in having a go at a

novel based on the programme. I was

pleased because I thought to myself,

“Great - someone else has done all

the hard work.” I sat down to read

these scripts and they were quite

entertaining but after a while, I

honestly thought that some of it was just

rubbish.

What

do you mean?

There was one part when

Bergman said something like, “My

God! His brain has swollen to three times

its normal size.” Well, I thought,

where did it go to? It just didn’t

make sense! To say that the brain had

swollen considerably would have been

alright, but three times is just stupid.

Another line was something like,

“His blood’s frozen

solid.” Now I know you need drama

and excitement and all the rest but it

should, to my way of thinking, be

plausible and some of these stories

weren’t.

|

|

| Did

you watch 'Space:1999'

on the television? Yes I did, although I have to say

that it got pretty ghastly towards the end of the

series. That is always the problem with a

continuing series of television programmes or

films, or even books for that matter. You tend to

re-use old ideas or borrow ideas from other

sources and it all looks a little tired.

'Star Trek' was the same and I love that

myself, but it happens there too.

The problem with 'Star Trek'

(in all of its incarnations) and 'Space:

1999' was the kind of village mentality:

everybody knows each other and looks out for

their neighbour and it’s an idealistic way

of life. With 'Space: 1999' in

particular, I felt that once they were off on

their journey there would have been more unrest

amongst the Alphans and I tried to put that into

my books. I mean, after a while, I would have

said to Koenig, “Who are you to still be in

charge of it all? Let someone else have a go or

we can run things by committee or

something.” Dramatically, I think that would

have worked very well because there would be

conflict and conflict brings drama.

The later episodes were

disappointing. I know that when they came on, I

was surprised that there were new characters who

I had never seen before and characters like

Bergman were gone without any explanation. It was

a shame because I thought Barry Morse was very

good.

Were you

ever invited to the studios or taken to any

special screenings of the programme?

|

|

When I was given

the job of writing the books, I was taken

to a screening in London with the other

writers who were doing the books. I think

it was a cinema in Marble Arch and I saw

four or five episodes of the programme. I

was really impressed and thought that the

idea of doing them as books would be

quite exciting. The problems really came

along when you saw it in print. The

actual scripted words were sometimes

terrible. All criticism aside, I

thought the programme itself was

excellent and very entertaining, which is

what it is all about I suppose. For me as

a writer, I felt that for the novels the

original scripts would need some

alteration as well as something extra of

my own. For example, there was a sequence

in one of the episodes when Koenig walks

down one of the corridors and into Main

Mission. There was no dialogue but

because that Main Mission set was so

impressive it held your attention. On the

written page of the script that I had to

work from it just said, “Koenig

enters Main Mission from an adjoining

corridor.” That was it. I had to

fill that scene out to make it

interesting for the reader. Between that

and the various scientific

inconsistencies, I decided that for my

adaptations I would use the scripts only

as a basis for what became almost

original stories and I think that it

worked better that way. It sounds a bit

big-headed, but I thought,

“I’ll do it my way.”

|

|

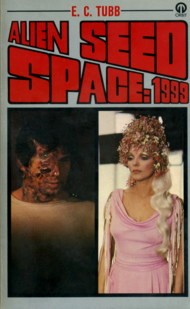

| When I had done the books

based on the scripts for the series, the man who

was doing the editing for the company publishing

the books said to me that they had lost the

contract to do further books based on episodes

but that they still had the rights to do a couple

more using characters and ideas from the series.

He asked if I wanted to have a go so I said,

“Yes.” I was hoping that they would be

so well received that they might be used as

actual episodes of the programme itself. So I did

a couple of 'Space: 1999' novels which

were entirely my own stories, and then the

publishers asked me to do a final book, 'Earthfall',

as they were still contracted to publish one

more. On this one, I was allowed to end the

series in written form as I thought it should be

done. As a writer, it was quite a challenge for

me and very enjoyable because the idea of the

series itself was a good one. The concept for the programme was

interesting, but quite constricting for a writer

like myself who tried to be as scientifically

accurate as possible. The Alphans were supposed

to be travelling at the speed of light or

something and then every species they meet talks

English - it could have been a crab sitting on a

rock or something and it turns around and says,

“Hello, Commander Koenig. We’ve been

expecting you.” I know the characters have

to communicate but they created an idea which

gave them many problems in terms of realism and

scientific accuracy.

I was far happier with the original

stories I wrote for 'Space: 1999' and I

was especially pleased with that last one,

because I had the chance to really do something

interesting with the Alphans, projecting into the

future where they have had children, returning

them to Earth and all of that. I tried to

re-address the scientific failings of the series

and add a bit of human interest as well.

|

|

Did

you ever have the chance to discuss your

thoughts with any of the actual writers

for the programme? No, never. I was sent

scripts to work from and that was that. I

never met anybody involved with the

writing of the actual programme at all

but I think I would have liked to. I

think that I must have done alright

because the books sold well and were

quite popular.

Are

you aware that your 'Space:

1999' novels are

more highly regarded than the others

amongst fans of the series?

No, I wasn’t, but I am

very pleased to hear it. I don’t

know why because all the authors were

from similar backgrounds and I actually

knew a couple of them pretty well. One of

the writers flaked out. I think I

remember that he had the same sort of

problems with the original scripts as me

but couldn’t (or didn’t want

to) overcome the problems like I did. I

think it was Brian Ball. We all met at

the screening and we went for a meal

which was all very nice, but then we just

went off and did our own thing.

|

|

| Were

you sent any photographic reference to work from? No, I don’t think so. I was

very impressed by the design of the Moonbase

itself and the costumes and, of course, the

Eagles which I thought were very good. I

didn’t have to describe any of those things

too greatly in the books because it was obvious

that the reader would be more than familiar with

what they looked like from the series itself. I

was sent a brochure or something which gave me an

outline of how Moonbase Alpha itself was set out

and also which uniform colours denoted which

role: white was medical, red was Main Mission

crew, and so on.

Do you feel

that your own novels and stories would translate

well into television? The 'Dumarest

Saga' in particular has all

the elements for an exciting long-running series.

I’m not sure. I think one

obvious failing in all television and film

science-fiction is that you have writers who have

little knowledge of science. But on the other

hand, you can’t have scientists or

astronomers attempting to write television

programmes because they don’t know anything

about the business of making dramatic

entertainment. I will admit that it is hard

because, obviously, television programmes are

always meant to entertain (and 'Space: 1999',

'Star Trek', 'Battlestar Galactica'

and all the rest certainly do entertain because I

watch them all myself), but things do stand out

sometimes as being written by someone without

even the basic understanding of, say, light speed

or time travel as a concept.

You also have the problem of other

people then using your ideas in a way in which

you never really wanted them to be used. I used

to laugh at the different covers that would

appear on my Dumarest books, so I can’t

begin to imagine how I would feel if somebody was

making a film or television series of one of my

stories. I think it must be difficult for people

like Stephen King who create these characters and

then a film-maker changes this, that and the

other. I suppose the financial rewards ease

things a little.

Also I have never actually liked the

term 'The Dumarest Saga', that was

invented by the publisher and it just stuck, it

wasn't something that I would have chosen.

|

|

Do

you deliberately use certain words as a

kind of trademark, I always noticed that

'Tintinubulation' seems to appear

somewhere in every Dumarest novel. Really (laughs). No thats

not something that I do - or was aware

that I did. I'll have to look out for

that now.

If

Dumarest were to be made into a film or

television series which actor would you

see in the role?

I'm not

sure, but theres an actor in 'The

Bill' who plays a character called

Frank Burnside (Christopher Ellison), who

facially looks like the character to me -

he has that intensity.

|

|

| Speaking

of other television series, are you aware of the

striking similarities between 'Battlestar

Galactica' and your

Dumarest novels? I know what you mean, with the

Cylons in 'Battlestar Galactica' and my

characters the Cyclan in the Dumarest books: in

both cases, they are the villains and are sort of

robot-like. The heroes in 'Galactica'

are searching for Earth and so is Earl Dumarest,

my hero. However, I wouldn’t say that I was

ripped off or anything because we all use

different ideas and influences that we pick up on

our way. I remember an old saying we used to have

which was, “Science-fiction is a pool in

which you dip.” A great many fantasy stories

are about a search or a quest to find something

or someone, or in this case, somewhere, so I

can’t claim to have created that idea. The

Cylons were actually robots but my characters,

the Cyclan, are only robot-like because they are

based on the law of pure reasoning, like Vulcans

in 'Star Trek' really.

I actually quite enjoyed

'Battlestar Galactica' but there was all

sorts of ridiculous stuff in there too. Look at

those pilots in helmets with a ring of lights

around the face piece. Why, in total darkness,

would you want little lights just in front of

your nose?

Even though

you are a serious science-fiction writer, you

still talk as if you are a fan of all this type

of thing.

|

|

Well, that’s

because I am a fan. I can pick holes in

it all and that is half of the enjoyment

of it. I tape 'Star Trek' if

I’m going out and I always look at

the films when they are on the

television. Science-fiction has always

meant a great deal to me. Like

yourselves, I used to organise

conventions although in my day it was a

different sort of fandom to what there is

now. My original taste of

science-fiction came in the 1930s. It was

a time of depression and those stories

gave me hope and a view of the future

which wasn’t as bleak as the one

other people might have had. Then the war

came along and it shook everything up. Of

course, there was a great deal of death

and unhappiness caused by it, but in many

respects it was a good thing, because it

pushed people into space through the

development of rockets and missiles, and

medical science moved forward in leaps

and bounds.

|

|

| When I first met up with

others who had the same kind of interests, I was

so pleased because I could talk about rockets and

satellites and all of that without being branded

a nut-case. As a

science-fiction fan, I write stories that I want

to read myself and, in fact, I do go back and

read all my old books because I find them very

entertaining. I suppose I imagine that other

people who share my enthusiasm for

science-fiction will also be entertained by the

stories that I write, and if that is the case,

then I am delighted.

* *

*

|

|

|