| Ian:

Well I’d always been interested in the film industry

but I had no idea how to get into it, so I found myself

working in a factory in Maidenhead doing all the

electrical wiring on missile testing systems. Then one

day my father mentioned that Gerry Anderson had come into

his shop to buy Cuban cigars, this was at a time when

they were making ‘Fireball XL5’, so I

got my dad to introduce him. I told Gerry that I was

doing electrical work but wanted a career in films and he

said ‘Well come and see our electrician because

we’re about to start a new show called ‘Stingray’

, and if he thinks you’re OK there may be a vacancy

for you’. And so that’s how I got my start. |

|

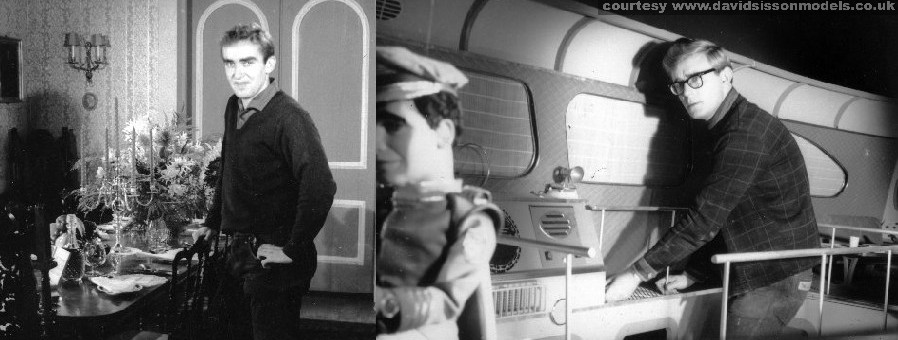

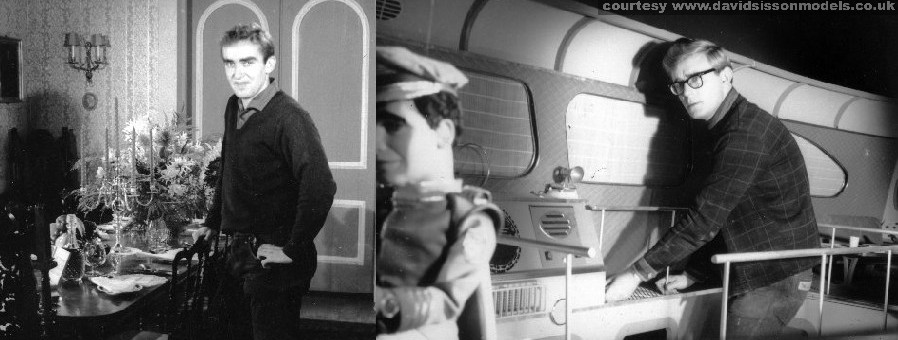

Ian's photographs

taken on the sets of Stingray.

Above: Director Alan Pattillo looks into the Stingray

bridge set. |

David:

When you joined it must still have been a very small

company.

Ian: Yes, they’d just moved from one side of the

Slough Trading Estate to the other. From Ipswich Road

where I think they’d done ‘XL5’ and

such like, to Stirling Road which was right next to the ‘Mars’

factory - so we used to get the nice smell of the

chocolate bars being made each day!

It wasn’t what you’d call a proper studio as

they were basically single-storey factory units and there

was no height in the ceiling. So that’s why they

later hit on the idea of digging pits in the floor to put

the camera and the camera crew in, so the stage floor

then became the set level giving us more height above |

|

Left; Ian in the

full-size set for the episode 'Tom Thumb Tempest'

and Keith Wilson prepares Stingray for action. |

David:

So you were purely an electrician on ‘Stingray’?

Ian: I was just an electrician but I used to help

out any way I could on the stage because I was interested

in the production. Whereas someone else might have just

done his bit of the job and then gone and sat in the

corner, I was always going on and helping the effects

boys out. I’d got electrical experience and used it

to get in the door, but I didn’t just want to be an

electrician.

I’ve always been quite good at art, even back at

school there was talk of me going to Art College but it

never happened, so after ‘Stingray’

finished and ‘Thunderbirds’ began I

managed to get myself transferred to the Art Department. |

|

David:

What exactly does the Art Department do and how long did

you stay there?

Ian: I think I was probably in that

department for about six months. Basically they design

and then organise for the sets to be built, run the

decorating for the sets, what the backgrounds are going

to be, all in consultation with what the director and the

producer wants and depending on what the action calls

for. Then when the set is built it has to be dressed. So

if it’s a room they have to decide what ornaments

they want in it, what pictures you want on the wall, what

furniture to use and of course does it suit that period

or the style of house. So in many ways the decisions the

Art Department makes sets the tone of the whole picture.David: ‘Thunderbirds’

started as a half-hour program then expanded to be an

hour long. I assume at this stage they had to take on a

lot more staff, or open up more stages to shoot on.

Ian: Yes they did, I think they expanded

into the buildings next door if I remember correctly. We

had two quite large buildings, one was for the puppets

and then we had one with three stages for the special

effects. Two of those stages were for shooting the main

effects and then one was what we called ‘The Flying

Unit’. Peter Wragg usually directed this and it had

the rolling road and the roller backing on it.

|

|

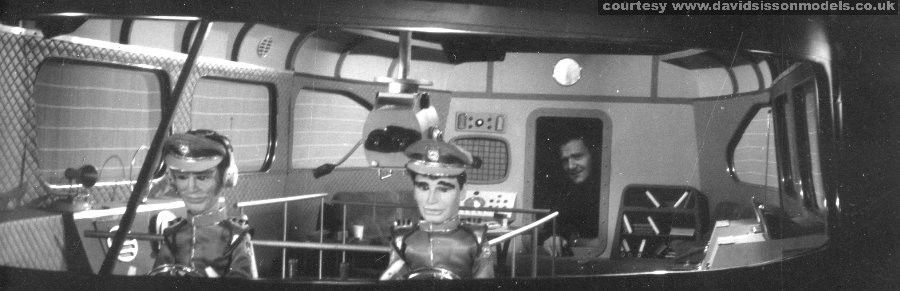

| Above left; Ian

keeps his eye on the assistant holding the model's

support wires |

David:

Was it your idea to now get into the Special Effects

Department?

Ian: Well yes

and no. They had fallen behind on ‘Thunderbirds’

because the special effects were far more complex than

what had been done before. They had actually fallen well

behind and the only way they could really catch up

was to start another unit.

The idea was for Derek Meddings (the Special Effects

Supervisor) to come back onto the studio floor, because

at that time he wasn’t on the day-to-day filming he

was off doing the overall designing and organising of

everything. So they asked us for volunteers to man this

new unit and so that’s how I started, working

directly with Derek, which was great because he taught me

a lot.There was a chain of command, Derek would be

at the top and he designed everything and did the

original concept. Then there would be a couple of other

guys below him, one of which would be Mike Trimm who

helped design models, and then below them there would be

the directors of the three units doing the day-to-day

work. And then below them they would have their crew of

normally about three or four guys.

|

|

David:

Did they pick different crews each week?

Ian: Mostly when you started with a crew you would

stay with them. Jimmy Elliott was one of the long-time

crew directors and Shaun Whittaker-Cook (pictured above)

was another and normally if you started with one of those

you would stay with them.

Shaun Whittaker-Cook was very ‘arty’ and very

posh compared to the rest of us. He didn’t use to

walk he used to ‘shuffle’ across the floor

(laugh). He was a lovely guy but he seemed a bit out of

place compared to the rest of us, a bit of an odd-one-out

really but he was about ten years older than most of us.

Jimmy Elliott was also a bit older and he was a real

character; one of the funniest men I’ve ever met in

my life.David: How was Derek Meddings to work

with, was he a good boss?

Ian: He was good. He was hard - he was one of these

that always used to say to us ‘Anticipate my next

move’. So in other words if I need a screwdriver in

my hand have that screwdriver ready to give to me, so

when I hold out my hand its there.

He was a hard taskmaster, he really could be, but he had

a lot of pressure on him because we had a schedule to

keep, and we had to get it all done, but in other ways he

was marvellous.

It was

quite funny because Derek was one of these guys who

always looked smart and never got dirty. At the end of

the day we’d be looking like tramps and Derek still

looked smart, I said ‘I don’t believe you

Derek, look at the state of us and you look

perfect’. The truth is he was probably as dirty as

the rest of us because he never shirked getting stuck in,

he was usually the first in there but he just always

looked clean and smart!

He was

also a great guy for thinking up shortcuts, that’s

what he was very good at; he was great at getting things

to work.

|

|

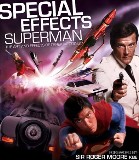

Above, the Monorail

train in the Thunderbirds episode 'Brink of

Disaster'.

SFX Supervisor Derek Meddings centre front. |

David:

How would you start each day, would you review the film

that you had shot previously?

Ian: Yes, you

usually went into rushes and saw the film from the

previous day (or even earlier that day) and decide if it

was passable or if we had to re-shoot. I must say that

the operation became pretty slick because you had a good

team of boys who had been there some time and we were

usually pretty good at what we were doing. There were

some re-shoots because you would go to rushes and maybe

see some silly little thing that you didn’t like and

if the set was still there then you could re-shoot, but

often the set wasn’t there and you had to evaluate

if it was worth rebuilding. Once again it’s the old

thing of schedules and money, because you had to stick to

a certain schedule and get a certain amount of shots done

each day.David: Did you usually manage that

or was there a lot of overtime?

Ian: There was

a reasonable amount overtime, it would come at times when

you’d get the odd episode that was probably a bit

trickier than normal, say like ‘Attack of the

Alligators’. I think we actually worked day and

night on that through a weekend because we were using

live alligators in the water tanks. Those alligators - or

crocodiles I believe - were quite difficult to control.

When we put them in the tank they would disappear and you

wouldn’t see them for hours at a time, and then

suddenly they’d come up and all you could see were

their two eyes. Obviously for a film you wanted to see

more of them than that so we tied them to the puppet

control poles and pushed them out into the middle of the

tank, so that you could see more of their bodies,

otherwise they just didn’t want to perform. Maybe we

weren’t paying them enough (laugh).

These things varied in

size from about two-feet long to one that was four-foot

long; that one spent most of the day sat in a box at the

back of the stage and we covered it in wet rags to keep

it moist. Over a period of several days you would forget

that it was there then one day someone shouted ‘Look

out’ and we turned round to see this big crocodile

walking across the stage – which cleared of people

very quickly!

Then there was the day when they were shooting some

publicity photographs with it and a puppet of Lady

Penelope. The puppet was standing right next to it and

this crocodile was absolutely static, it was just stuck

there without a single movement for what seemed like

hours. Then suddenly it just turned round and got hold of

this puppet and violently shook its head several times

and there were bits of puppet flying in all directions

(laugh). And I can remember the puppeteer, who was

Christine Glanville, was in tears because this puppet was

her baby. Poor Christine, but that’s the fun of

filmmaking!

|

|

David:

Was everything you did storyboarded?

Ian: Yes, that was very important, and we had to

keep to those storyboards especially with model work like

that. Now and again you may deviate a bit but basically

that was our shooting bible.David: Was

there any competition between the units to see who could

get the best shots?

Ian: Oh yes, definitely, it was very competitive

in that way and quite honestly we really loved what we

were doing from a work experience. We were all still

young and impressionable in those days and it was

fantastic - and it wasn’t like work in many ways.

David: Did you have any particular

friends on the crew?

Ian: Well I don’t know how they all

originally started but there was a group of guys who came

from the Victoria area in London, Bill Camp, Ken Turner

and Alan Berry and they became very good friends of mine.

Jimmy Elliott was a very good friend too, and at one

point I shared a house in Cookham village with Brian

Loftus, Ian Scoones and Keith Wilson - who sadly died

just recently.

All these guys were good friends, so much so that one

year a big crowd of us all went down to Spain on holiday

together. There were two or three different groups but it

was the sort of place where we just all got on.

David: Roger Dicken worked on ‘Thunderbirds’

for a bit didn’t he?

Ian: Yes, he dressed like a Rock-and-Roller and

was the most unlikely person that you would expect to

make animated models. He was very good at his job and he

was so into Prehistoric monsters, animation, Ray

Harryhausen, and all that.

But he lived on his nerves and Derek would come into the

workshop and say ‘Come on Roger we need that model

now’ and Roger would be getting all upset that it

wasn’t ready and the two would be arguing, and of

course we (the crew) were terrible and we would try and

wind both of them up just for the laugh. The pair of them

was so funny.

David: What sort of day-to-day jobs

were you expected to do there as an Effects Assistant?

Ian: Well it was a bit like a film school for

effects men really because we did a bit of everything, so

it was like a training facility. Because it was such a

small studio we could become involved in everything, we

learnt by looking through the cameras and sometimes even

help operate them. You learned more about lenses and such

like, leant about different camera speeds for different

shots, you were rigging stuff and doing scaffold work,

slinging lines across to fly the models. You would never

get that experience as a special effects technician

working on a big movie so it was very varied - plus the

explosives, the pyrotechnics, that was obviously a new

area to me.

|

|

David:

Did you have a daily target for how many shots you had to

achieve?

Ian: Yes we did, but don’t ask me what it was

as it did vary a bit. It was hard going, it really was,

we got there first thing in the day and we didn’t

stop. And the other thing was that we had to build the

sets ourselves, we didn’t have a construction crew

come in and build the sets for us - we did the lot.

It was building the sets, modelling the background, even

getting involved in painting the backings. Then you had

to dress the sets, like if you were doing a big street

scene you would be putting in the buildings and laying

down grass (using special grass mats) and then dress and

paint the edges of the road using lots of powder paints,

and dressing the landscape to get the distance on the

shots. It was very hard work and so by the end of the day

we would be covered from head-to-foot in dirt and powder

paints, and it got so bad that they actually had to

install showers for us because we couldn’t leave the

building in that state every day.David: So the landscapes were

literally just thrown together from a collection of bits?

Ian: Yes, all the rocks were sculpted from

polystyrene and we would have a stock of these, all

different sizes and colours, which we kept just outside

the stage door. And we would go out and bring them in,

set them in place by trying different ones and dressing

them to camera, thinking ‘That looks good’ and

sending someone to go and have a look through the camera

and tell you what it looks like. Then you would dress the

floor using a lot of silver sand, nearer the camera you

would use the very small-scale grass matting and for the

most distance stuff you would use coloured powders.

If we

were doing the road we would colour the roadway not with

paint but usually with grey and black powders. And you

would put in the wear marks in the road where the cars

had been; again doing it using brushes and powder paints

so it was quite artistic to do that sort of stuff.

|

|

| Behind the model

mountains we would have cutouts of painted mountains and

behind that we would have more mountains painted on the

actual backing. There used to be a lot of work involved

in doing it and we all used to jump in and get involved

with doing the colouring of the set, which often meant

changing the colour of the rocks if they didn’t suit

that particular story. The rocks might have been in a

desert the previous episode, or the Moon, so you had to

get a spray outfit out and change the colour to suit the

episodes requirements. We used to use different scales of

grass matting and lots of real stuff too, like lichen.

That was a great lifesaver because you could use it for

trees and hedges. For some trees we would build them from

real bits of small tree branch and then spray them with

this white adhesive material, I can’t quite remember

what the product was but it was a bit like the

snow-effect stuff we use today. Anyway we would spray

this stuff onto the branches to create scale leaves and

then spray it all green, and that used to work quite well

for us.

David: The sky backgrounds always

looked very good.

Ian: Yes, I’d say the person who did more of

those than anyone was Derek himself; he was a very good

artist because that was his background originally. He

started out by working with Les Bowie who was originally

a Matte artist and Derek was to have carried that on, but

then like Les he moved on to more general effects work.

David: Did you ever have problems

getting shadows on the backdrops?

Ian: We often had problems, if you could you would

do a dry run to see if you got a shadow, but that

wasn’t always possible. It was one thing that the

Lighting Cameraman had to deal with all the time. They

would often light to eliminate the shadow altogether or

have the shadow appear well after the shot, in other

words the shot was through and gone before the shadow

appeared on the backing.

|

|

David:

Who came up with the idea for the rolling backdrop?

Ian: The idea

wasn’t new as it had been used in films back in the

1930s, although it probably just had a bloke with a

handle and not a motor like ours. We also had the

horizontal one, which had an attachment to it so that

there would also be a foreground one that ran at a

slightly different pace.

I can remember working on the episode where the big plane

(the Fireflash) had to come down and land on the

vehicles, that was a pig to do, getting it to land and

everything to work right. You had the models on thin

tungsten wires and if one of them broke your model would

go ‘whoosh’ past your head (laugh) and you were

picking up the pieces, then into the workshop to get the

glue out. But it did all work out well in the end.David: Did

the belts ever come off?

Ian: We did occasionally have problems; the sky

backing was the worst one because obviously gravity was

pulling it down. It was made from rubberised canvas and

it was on rollers that you could tension at each end to

hold it up there, but it did move down. At a later stage

it was modified and wheels were put around the top to

support it and stop the problem.

David: I guess that one of your jobs

would have been to light the Jetex motors, I assume that

they were ignited manually?

Ian: Oh yes the Jetex motors, we used those in the

models to kick up dust under the vehicles as they went

down the road. We probably sent Jetex shares soaring at

that time for the amount we used (laugh). Basically it

was just an off-the-shelf product made of cheap

bronzed-metal, it came in two halves and it had a spring

clip on the top that you would latch over. You would put

the two Jetex rocket fuels in there, half pellets (bit

like slug pellets), and then you put a fuse filter in

there, coil it up and poke it through the end, put the

lid back on, clip it over and fix it into the vehicles

with little spring clips. It was usually lit by hand, not

electrically, usually by leaving out a trailing fuse or

by poking a light underneath. We’d dust the road

with powder paint, lit the fuse, turn over the camera,

and then pull the model car down the road and so

you’d get all this dust flying up, which gave it

some action and made it look more realistic.

David: In Alan Shubrook’s book

Century 21 FX: Unseen, Untold there’s a good picture

of you trying to catch the big

Thunderbird 2 as it leaves the

launch ramp (feature film version). Was catching the

models a common job?

|

|

| Ian: Yes, you

usually were due to the space restrictions in the studio.

If you were shooting at high speed and you wanted a model

to come through fast you had to get it up to speed very

quickly. We pulled the models through on running wires,

we had a running wire above, a very taught piano wire,

and we used to run a tube along it with the model hanging

from what we use to call a crucifix with screw-eyes in.

That model had to get up to speed very quick,

because you’re shooting at high speed, and

you’ve got to stop it quickly as well. So these

things were hanging there on very thin tungsten wires and

so we use to try and catch them, to save them from

smashing into the tower that was supporting the wire and

also to try and stop the wires from breaking. Because you

often wanted to do a second take and you don’t want

to have to rewire the model again. So it was very

important that you caught this thing. David: Did

you ever build any of the models?

Ian: No not a

great deal. I wasn’t involved in the model workshop,

I used to get involved in repairing them but I

wasn’t actually one of the model makers. If I

remember rightly Ray Brown ran the Model Workshop and

there was also Peter Ashton and they were both very good.

David: Apparently some of the models

were made from Balsa wood at the beginning to keep them

light, before fibreglass ones were used?

Ian: That may have been the case, but Balsa wood

didn’t necessarily make the models lighter because

you can’t always get the very thin shapes, or the

finish on it, that you can get with a fibreglass model.

And the fibreglass ones were actually pretty light.

The

worse one was Thunderbird 2, because it was so big

it was quite heavy and then on top of that every time it

crashed down on the floor it was a case of rushing it

into the model shop for a quick repair with Cataloy (car

body filler) and then back onto the set. As time went on

this model actually got heavier and heavier (laugh) and

it was falling off as much as it was staying in the air!

So it was almost counter-productive to repair it in this

way, but that’s how it happened.

David: I guess the models were

designed to look good and so were not always very

practical. I was looking at the Crablogger

photos and thinking how was such a massive model moved

through the scenes.

|

|

|

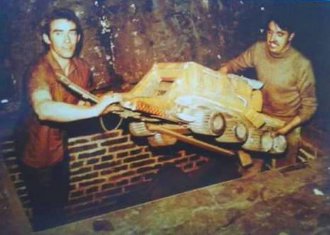

Filming the

stunning 'Crablogger' miniature for the Thunderbirds

episode 'Path of Destruction'. The vehicle is now

out of control and plows through the town of San

Martino. The effects camera crew are in a pit

that was specially dug into the studio floor to

allow the camera to be as low as possible when

filming the models.

Left;

Ian helps to remove the wrecked model from the

pit.

|

|

|

| Ian: Well if we

didn’t use a wire there were often times when we

used to just push these models in, we would have a rod

and hide it down the back and push it along. Or we would

have a rod going down through the set and someone pulling

it through. It was

harder to get the models to turn, the vehicles all had

small axles on them with a bit of steering so the wheels

could turn and suspension, which was usually done with

foam rubber, to get the movement. Basically we had a slot

in the centre of the set and they were pulled by someone

underneath, or someone at the side.

We had a system (which worked on the overhead models as

well) that if a model was on a wire and we again needed

to get them up to speed we would use bicycle wheels, and

we put a little drum on the bicycle wheel so it was like

a gear, so it was 2:1 or 6:1 or something like that. So

you pulled the cable on the small drum and just ran with

it and the model wire was attached to a large drum, so

this gearing allowed the model to get up to speed very

quickly.

There were times when you had a very long run and you had

to run out the stage door and into the corridor just

pulling this model. The fact is we didn’t have the

time or money to get more sophisticated than that, it was

pretty much all manual where possible. We did have motors

on a few things - but very few things!

David: When people talk about wires

they often think of just fishing lines.

Ian: It was

fishing lines, steel cables, string, it was all different

things depending on the time we had. We had one

particular cable that we used a lot to pull stuff on and

that was called a lay-flat cable, which was very thin

bonded wire. We used that mainly because it didn’t

stretch and we got better feedback through it, whereas if

you used a fishing line it would be very bouncy.

With the tungsten support wires we could feed electrical

power down to the models, but if you used too much power

they would just burn out and snap and down would go the

model. So you had to know just how much you could use

because most of the time we over-ran all the bulbs in the

models, in other words if it was a 6-volt bulb we would

run it up to 12-volt or even more to make it as bright as

possible. But by doing that it became quite easy to use

more power than the tungsten wire liked then puff it

would burn-out, especially if it was under tension which

it usually was.

|

|

David:

How did you attach the wires to the models?

Ian: A lot of

the time if there wasn’t a little hole or something

we would put little dress pins into the model, and just

go round the pinhead. But where you had to be careful

with tungsten wire is that you mustn’t kink it, you

must not turn it back on itself, or it just breaks very

easily. That’s actually how we used it, once

we’d run a length out we would just kink it and it

would break. But obviously you didn’t want that to

happen on the model so you had to be very careful how you

tied it on and we used to use things like a

Fisherman’s knot where you wouldn’t kink it.

With some models, like Thunderbirds 1 and 3,

you could attach it with a single wire through the nose.

On the take-off shots we use to try and get it so that

the support wire was directly above the model so that it

wouldn’t want to move in any other direction. But

sometimes you did see the odd one where the model used to

spin a bit, but we usually got it looking pretty good

with the rockets firing underneath.David: Did the person holding the

model activate the rockets?

Ian: No that

was usually done by someone else. On some models we had

to run the feed down the wires but at other times, like

the Thunderbird 1 take-off, we would put the

electrical ignition up through from underneath the set

and into the rocket pod, so that wasn’t actually

attached to the model and that was the easier way of

doing it. (This can be seen in some episodes as a

burning wire protruding up from the landscape set.)

David: Has anyone ever pointed out

to you that the four rockets that fired when Thunderbird

2 landed, or took-off, were actually

put into the holes for the legs – not the holes for

the thrusters!

Ian: I’ve never given that any thought to be

honest, and I don’t think anyone else ever did!

(laugh)

I mean Derek designed all these models but he wasn’t

actually very practical as such, so perhaps he

didn’t think of it and nobody else did.

David: Were you often pulling the

models along?

Ian: Oh yes I

was, there were certain people who were good at flying

the models and pulling them along. I seemed to have a bit

of a talent for it so I often became one of the

operators; another person who was good at it was Peter

Wragg.

This wasn’t always a good thing because you usually

ended up on top of the tower holding Thunderbird 2

or one of the others. I keep harking on about Thunderbird

2 because it was ‘The Pig’ of all the

models, it was a nice model but it was so big and

heavy and you used to be standing out there holding this

thing from the wooden crucifix (with the four wires

hanging down) and you were standing out on a plank that

was bending under the weight – it was almost like

walking the plank on a Pirate ship! And not only that but

this plank was tied to a tower, and we used to put a

couple of big steel oxygen bottles on it to

counter-weight it, but the trouble is that often you were

so far out that the tower was starting to move a bit. So

you were on a plank that was bending, on a tower that was

moving, and you were out there holding a very expensive

model with your hands actually shaking from the weight.

And you also had to hold it most of the time because they

were colouring the wires – we had powder puffers,

and powder paints with different tones and they had to be

applied to match the backgrounds. And so with a

combination of lighting, the puffers, powder paint and

anti-flare spray we used to get rid of the wires, because

in those days we didn’t have CGI to get rid of the

wires we had to do it live on the set.

|

|

David:

I think Derek also referred to Thunderbird

2 as being a bit of a pig too!

Ian: Well Thunderbird 2 had the highest

failure rate just because of its bulk. If it had been a

real vehicle I don’t know how it could have ever

flown quite honestly (laugh) but that probably goes for

all of them up to a point. Thunderbird 2 was the

hardest one and it was the one that was used more than

any other, it was in every episode and with different

Pods.David: Talking of Pods, how

did it actually stay in position, did you just normally

jam something like Plasticine (modelling clay) into the

gaps to hold it?

Ian: You know I can’t actually think back on

this one, I was hoping that you wouldn’t ask me that

one (laugh). The Pod was fibreglass and too heavy for

Plasticine to hold it. There was some sort of bracket but

I can’t remember if it was underneath or inside, but

we did use something to secure it.

David: In a lot of these

behind-the-scenes pictures we can clearly see the roof

and the crew are actually up against it.

Ian: Oh yes that’s right, we were up in the

roof and all the heat just went up there too. Because we

were shooting high-speed there were two or three times

the amount of lights as normal and it was HOT, most of

the time we just wore shorts and nothing else and the

sweat was just pouring off us!

David: Did they have extractors

installed?

Ian: There were extractors there but as you know

extractors never seem to do what they claim. I’ve

been going into different buildings all my life,

especially on film sets and big stages like Pinewood and

Shepperton, and you hear the extractors roaring away but

the smoke and fumes seem to stay exactly the same. So yes

they did have extractors, but because we used to need

black smokes in there - which to make black smoke you

have to burn something, usually from smoke candles - and

white smoke and do explosions with naphthalene the

atmosphere inside those buildings was pretty grim at

times.

David: Did you usually wear masks?

Ian: We did have masks but at times they were just

impractical to use. We used to do explosions and because

the stuff was so close to us we all wore protective gear,

helmets, facemasks, fireproof jackets, because we were

really close to these things. It wasn’t like the

explosion was in the field next-door you were almost in

amongst it. It was miniature stuff and it was right close

to camera and we were doing it in buildings that really

weren’t properly suitable for that type of work.

So at the end of the shot it would be ‘CUT’ and

there were times when you just stood there and you

couldn’t see where you were, you didn’t know

which way to turn, because the smoke was so thick. And

you had to wait for someone to open a couple of big doors

and put on some fans to blow it all out of the building.

David: So how big were these

explosions and did you mix them at all?

Ian: Well some of them usually used to hit the

roof – although the roof wasn’t that far away!

We were all allowed to do it and some people got into it

more than others. I used to love learning how to mix it

up. There was an art to doing small explosions as opposed

to the big ones; I think its harder in many ways.

|

|

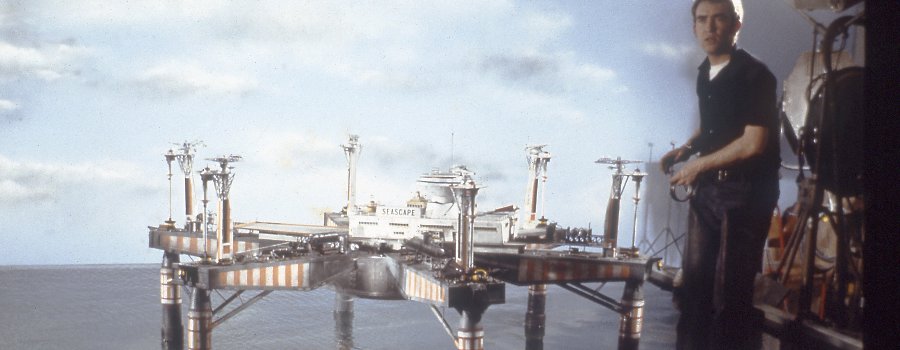

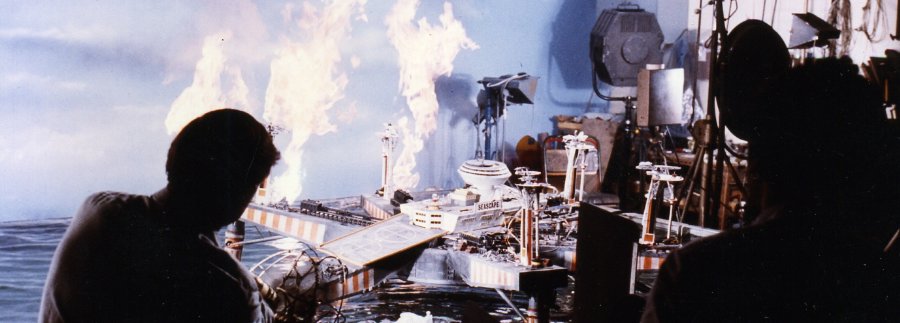

Ian standing in the

water tank, as he prepares the Seascape oil rig

model

for the Thunderbirds episode 'Atlantic Inferno' |

David:

Derek sometimes called them ‘soft explosions’,

did they have much power to them?

Ian: Well they could have power. When he says

‘soft’ it usually means a pyrotechnic which is

a powder, like black powder etc. And when you say

‘hard’ you usually mean high-explosive, which

is dynamite, plastic explosive, and things like that. You

can make a little charge quite dangerous, or bigger, by

just ‘tamping’ it. Tamping means either

wrapping it much harder or putting it in a confined space

so that it has to work harder to get out.David: And they worked fine in the

water tank?

Ian: Yes they

did work in the water if you could keep them dry before

you let them off, which we did in various ways like

putting them in bottles and such like.

David:

I noticed in some of the shots in ‘Captain

Scarlet’ that when an explosion

occurred all the powder paints on the floor would lift

into the air, which looked very realistic.

Ian: That was

basically the shockwave from the explosives, sometimes it

used to work for us and sometimes it didn’t and that

used to work quite well. Sometimes things happen better

than you think they would, and occasionally unexpected

things would happen. At times you can spend hours trying

to get something to work and then something else would

just happen spontaneously.

|

|

| John Richardson who did

the first ‘Omen’ film, where they cut

the head off on the pane of glass and then the head spun

on the glass, said to me ‘We didn’t do that, it

just happened’. Everyone said that it was

‘Terrific’ but he said they just got lucky!

Funny enough I thought Derek was one of the luckiest

special effects guys I ever met because when we did

things we would say to him ‘Shall we do this, and

that, to make sure that it works’ and he would say

‘No forget about it’ and it would work just

fine. But if you did it the next day it

wouldn’t work at all, he was lucky that way. David: Did things ever go wrong?

Ian: Sometimes.

I remember a time on ‘Stingray’ with Ian

Scoones when there was an underwater shot where one of

those Terror Fish was blown up by a missile. We

were filming through the fish-tank and we had this

missile coming in on a wire where it hits this model and

then goes BOOM. As soon as this happened we were to cut

the support wires to make the model drop, and that model

wasn’t rigged on the overhead wires but a horizontal

wire because the idea was that it was easier to cut that

wire and get the model to fall cleanly. I can remember we

spent hours getting this thing prepared, it was a real

tricky shot to do, we got it all ready and then the shout

came ‘Turn over’, so the cameras are running

but then something was wrong so the call went out

‘CUT, CUT’. So Ian thought it was his queue and

cut the wires - silly boy. Old Derek was livid and shouts

‘SCOONES YOU’RE A C**T! (laugh).

It was hilarious, but we all ended up doing things like

that, it had to happen, it was inevitable when you were

working at that pace. Sometimes we would do five major

shots a day and it was a lot of work, and as soon as

you’d done one it was right strip it down, sling it

out, and get the next one in. But we did have fun too.

|

|

David:

They started making Thunderbird

feature films, do you remember much of this. You did

actually get a screen credit for ‘Thunderbird

6’, did that mean you got more

cash?

Ian: I can’t remember getting more cash (laugh)

but yes I did get a credit, prior to that not many of us

got screen credits. That was in the days when you go to

see a film at the cinema and only the special effects

supervisor usually got a mention.

I did a little bit of work on the first one, but I was

sort of in-and-out on that. The first film was more Shaun

Whittacker-Cook and Richard Conway, I would just come in

if they needed more hands on it – I remember being

involved when we were letting off all the fireballs with

the Rock-Snakes on Mars. |

|

Above; Ian (centre)

working on the set during the filming of 'Thunderbird 6'.

The camera shoots

through a partial model of the Tiger Moth wings to get an

aerial view of Lady Penelope's home. |

David:

So you couldn’t answer the question ‘Why was

Mars Grey?’

I mean they fly to the Red

Planet and it looks just like the Moon!

Ian: I

can’t answer that one, I can’t remember if we

had photographs of Mars at that time so we obviously

didn’t know if the surface was actually that red.

Maybe they did tests using different coloured surfaces

and they found out that it really didn’t work, or

perhaps it was the most practical and best looking for

that scene in the film. David: Did the team split

at this point because ‘Captain

Scarlet’ was being done around

the time of the later Thunderbird

film?

Ian: Yes, I

started on ‘Captain Scarlet’ but Derek

was going to direct the effects on ‘Thunderbird

6’ and he asked me to go on it with him. ‘Thunderbird

6’ was good because obviously the budget was

higher than normal and so you got to do things bigger and

probably better than you had done before. For example we

built a very big-scale motorway bridge out in a field

near to Booker Airfield at High Wycombe, so that you

could use the real background and sky as part of the

model shot as we flew the model Tiger Moth underneath the

bridge.

They also did it for real as they were still building the

M40 motorway at that time. They got a pilot, called Joan

Hughes, and she actually flew the plane underneath this

new motorway bridge. She wasn’t supposed to as she

was only supposed to taxi it and the Ministry man, who

was there at the time, went absolutely bananas (laugh),

but she was a brilliant pilot.

Of course we could repeat the stunt in miniature and we

used to fly our planes under the model bridge. But the

model plane was thrown out of balance quite badly by the

small puppet figures on the wings and it was very

difficult to get that model back into balance, as a

result it piled into the bridge on quite a few occasions.

David:

What did you think to the puppet programs?

Ian: I loved them, because at that time they were

something totally new, they became very big, they became

the ‘in-thing’ you know. In those days if you

said that you worked on ‘Thunderbirds’

then they really thought you were wonderful, and this was

in the days of the swinging sixties, and so we were quite

well thought of by everybody. It was fun, it was

groundbreaking really because nobody had ever shot models

like that before.

|

|

David:

With ‘Captain Scarlet’

they introduced the more life-like puppets.

Ian: Yes, a lot

of people thought that they lost something then. When we

first saw them we thought the heads were too small, they

were actually the right scale but I always thought they

were too small - and even looking at them now I still get

that feeling! And I think a lot of people believe that

that was a mistake to make them look too realistic, and

to have kept the characterization of the bigger heads, it

worked better for what they were.David: Here’s another daft

question but I have to ask. On ‘Captain

Scarlet’ the SPV

had tracks on the back that pivot down, but they were

never used. I wonder if it was an effect that

couldn’t be made to work?

Ian: I can

never remember those tracks going down at all, certainly

not in any of the episodes that I was involved with. I

think it was something that was possibly designed because

it looked good, but I can’t remember them ever being

used while I was there. I think comments were made by a

few of us at the time about ‘What are those tracks

for’, and people just looked at each other and

‘Well they do nothing so lets carry on’

(laugh).

I

remember one day that some comedian had gone up into the

roof and put two large eyes there and underneath had

written ‘Derek Meddings is a Mysteron’ (laugh).

But no one ever admitted to it.

David: I believe that you worked on ‘Doppelganger’.

Was it good to be working on a ‘proper’ film

with real actors?

Ian: Yes that

was good to work on, once again it was a bit bigger

budget than the TV programs and we had a chance to do

more things. I’d been at the studios since ‘Stingray’

so I was one of the longest serving members there and it

was nice to be getting into other things and doing

‘floor effects’, which is something that I did

in the later years, moving away from the model work and

into the big practical floor effects with real people.

You were meeting actors that you had only seen on the big

screen, like Ian Hendry, Patrick Wymark and Roy Thinnes -

who at that time was the star of an American series (‘The

Invaders’) and was a big name.

|

|

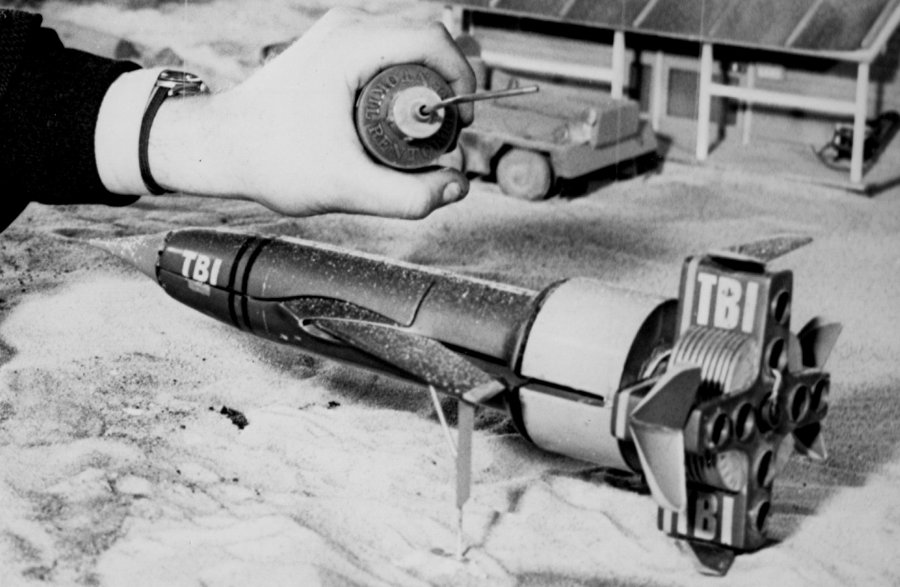

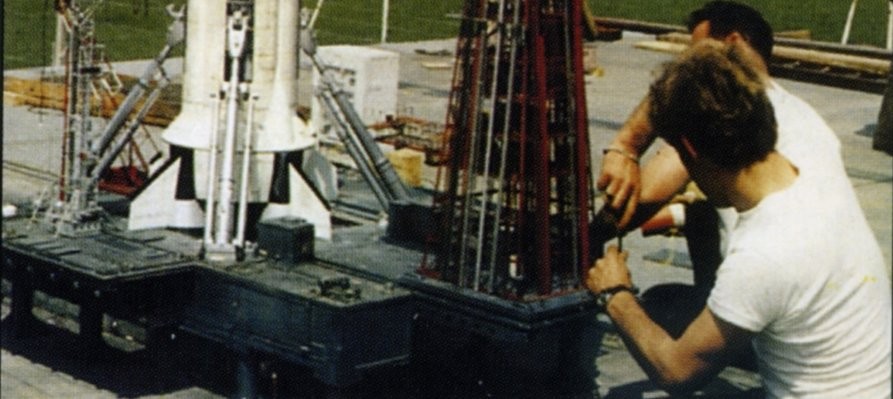

| Above; Ian prepares

the rocket miniature for launch, filmed outside to get

the real sky background |

|

| So it was more like the

glamour side of the business and nice to be doing it, and

once again the models were bigger and there was better

stuff to do. Like for the rocket take-off where we built

it outside between the two stages, and we had two big

40-foot towers with a ladder beam across for the rocket

to be pulled up on, so you were looking up at real sky

away from the Slough Trading Estate. Unfortunately

something happened on the first take and it got jammed on

the launch platform. When we fired the rockets the

support arms were supposed to jump back to release the

vehicle and then off it went. However when we were

shooting it the arms didn’t move, I can’t

remember exactly what the problem was but one of the

cables must have snapped. So suddenly we were sitting

there and found that we couldn’t move it, and those

rockets were going and once they ignite that’s it.

There were three 2-inch diameter rockets in that thing,

they we BIG, and they did quite a lot of damage. And you

couldn’t really put it out easily, just trying to

get up to the model in the first place was hard work and

then spraying it to try and put it out, by the time you

got there the damage was already done! David: Did you have any problems

keeping the miniatures in focus?

Ian: Yes you

did. One of the things you do is split your focus so that

you try to hold the background and foreground reasonable

well in focus. Because if you focus like say in a normal

film where they are focusing on the actors you can notice

that the background often goes soft, or if they’re

talking to a character in the foreground they can go a

bit soft. With ours, to try and make it look more

natural, we used to try and split the focus and to do

this we used to use wide-angle lenses all the time. So

rather than keep the camera still and put on a

narrow-angle lens, where you would have more of a problem

with focus, you would keep using the wide-angle lens and

just push the camera in closer to the set.

David: I think ‘UFO’

was the high point in the effects work, the Shado

Mobiles driving through the forest

looked pretty real.

Ian: I think

that over a period of time we had learnt little things as

we went along, how to shoot the models, how to make them,

what was the best scale, how to weight the models, make

the suspensions so they looked more natural, etc, etc. It

was something that had evolved. On ‘UFO’

I started on the models, because the effects started up

before the live-action, but then I moved more over onto

the live-action effects side of it. I was forever

backwards and forwards between Slough and Elstree with

the car loaded up with bits and pieces, explosives and

such like. In those days Elstree Studio, like Pinewood,

had its own in-house special effects department so I

always used to use one of their guys to help me out,

which was normally Trevor Neighbour.

|

|

| Filming the Shado Mobiles as they hunt for

aliens in the UFO episode

'Computer Affair'. |

David:

When these new models appeared on stage were there any

times that you thought ‘How are we going to make

this work’?

Ian: You used

to get certain ones that were a problem; the worst was

the UFO with the spinning top. We used to think

how the hell are we going to suspend this on wires, and

then keep it steady, because the only way to get a fixing

was from the top bit that didn’t spin. So we would

have a main wire from the centre and splay the wires out

– and sometimes put a wire out to the side to stop

it moving round too much. But it was a pain, every time

to fly that thing was a pain! Also aerodynamically it was

just totally wrong (laugh). On any model you would find

the centre of balance on but on that thing you

couldn’t – I mean if you just held it in your

hand it would be wobbling! |

|

David:

The flying effects were slightly different this time with

what looked like real clouds.

Ian: Yes, we

had a base layer of dry-ice and then we would mix it with

different types of smoke, two or three smoke machines

would be used as some would give you a better layer than

others. Plus sometimes you would send the smoke down

through the dry-ice to mix it, so that it would hang

there that bit longer. And you had to time it, and wait

till it was ready, and then you would say 'It looks good.

Turnover, go'. It worked very well. |

|

| Above; Ian feeding dry-ice and smoke onto

the set |

David:

I think that you had more space to do the ‘UFO’

effects as you had taken over the empty puppet stages.

Ian: I’m

not sure as I think there was an overlap at some point

with some puppet stuff still being done, as they may have

still been filming ‘The Secret Service’.

It was a shame really because they did still have the

opportunity to continue shooting puppets, but Gerry just

didn’t want to know as all through his life he had

wanted to shoot live-action. I think he made a mistake

then and should have found a way to keep shooting the

puppet stuff, trimming it down so that it wasn’t so

expensive. That way I think it could have carried on for

several more years. However you have to give him credit

with what it did at the time, but I guess he had a

love-hate relationship with the puppets and just wanted

to get away from them and do live-action only – and

he did shoot some good live-action stuff.David: Did

you see Gerry or Sylvia on the sets much?

Ian: You used

to see them daily. Old Gerry was marvellous because when

I first started he said ‘There will be times when

you are very busy and other times when you’ve done

your thing and are sat down having a cup of tea. I’m

not worried if I come in and find you’re having a

snooze in the corner because if you’re not doing

your job I’ll soon find out. So don’t worry

about seeing me and having to jump up and start working,

because if you have to do that then there is something

wrong.’ And he was marvellous like that. I got on

well with Gerry and I’ve got a tremendous amount of

admiration for him, he gave me my first break and he did

a marvellous job with all those films.

...........................................................................................

|

|

|

David:

When ‘UFO’

was coming to the end did you realise that it was the

‘last’ show?

Ian: It was

difficult to believe I’ll say that. I was one of the

last people there and I can remember having to chuck all

these models in skips and I actually ended up with a Thunderbird

2! We were throwing everything out because in those

days there wasn’t a market for film memorabilia, it

just wasn’t valuable until years later. I saw this Thunderbird

2 and I thought I’m going to have a memento and

so I said to Gerry ‘Could I have something’ and

he said ‘Take what you want’, and so I had it

and everything else was skipped.So I actually had this model but

unfortunately over the years I’ve lost it!

I have had fans of ‘Thunderbirds’

phoning me to say ‘We’re heard you have this

model would you be interested in selling it’. So I

went to look for it as I thought it was in the loft, or

down where I store my equipment, and I just couldn’t

find it. So I asked my wife and she said ‘I think

you threw it out during one of your famous

clearouts’ – can you believe me doing that?

David:

It would probably be worth about £50,000 now!

Ian: Tell me

about it (laugh). But I do now bitterly regret not having

that Thunderbird 2. I’d love to have it, not

necessarily to sell it, but just to have it. Because that

was an important part of my life, where I first learnt

about special effects. It was like a film school and you

were paid to learn these things, and it was so much fun

working on those models and it was so creative. I really

enjoyed it there and it was a great bunch of people. Good

days, they really were good days.

|

|

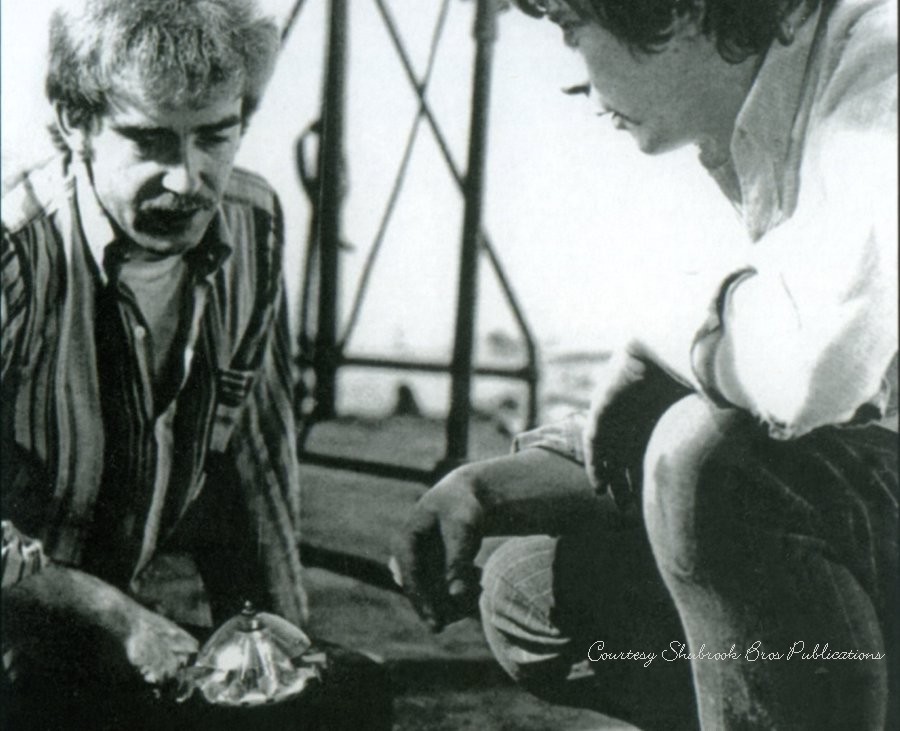

| Above left, Ian

examines a UFO miniature prior to filming |

I would like to thank the following

Ian

Wingrove for kindly inviting me into his home and

answering every question I could think of!

Dennis

Lowe

for his enthusiasm and taking the time to arrange and

film the interview. |